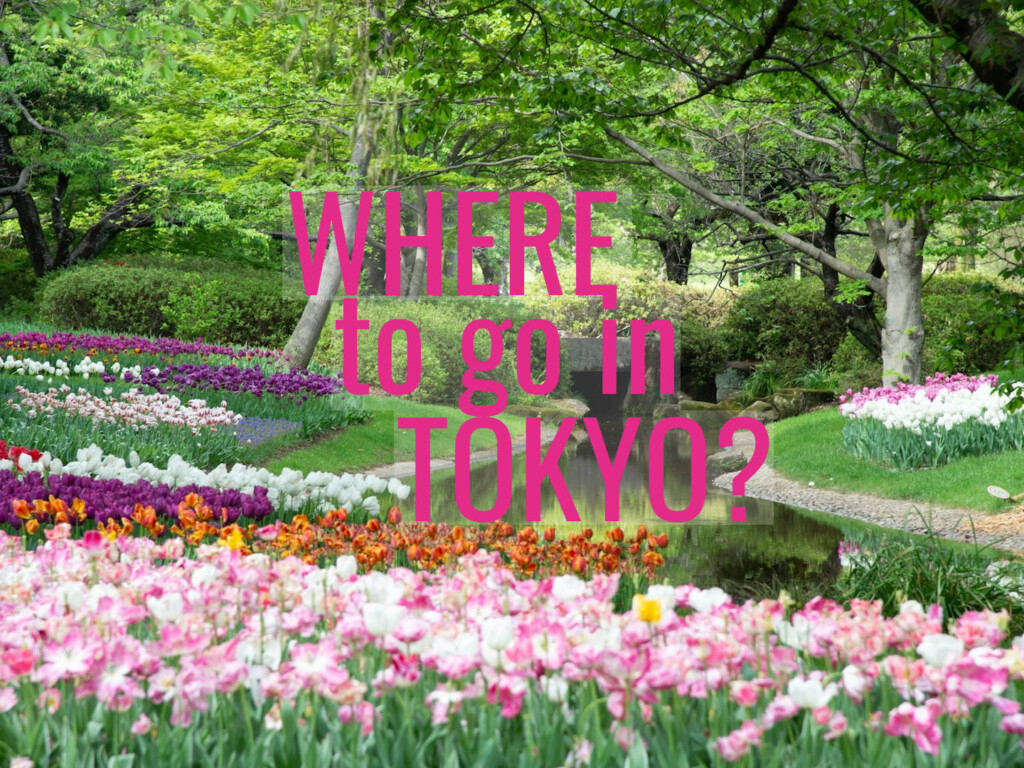

American cultural geographer picks three favourite places to go in Greater Tokyo

Japan fascinates Westerners with its rich traditions, hypermodern cityscapes, exquisite cuisine, and globalised pop culture.

With all of this packed into a moderately-sized country where people are at once cosmopolitan and polite, streets are safe, and train and bus systems form an Eighth-Wonder-of-the-World model of transportation efficiency, the siren call to travel to Japan becomes even more powerful.

Tourist websites list no shortage of “things to see and do” in the country that are no doubt all worth seeing and doing. But after visiting Japan — most often Tokyo — annually over the last 20 years, I have made a personal list of recommendations — places to go in Greater Tokyo — that don’t always appear on these websites.

The inside track

Ron Davidson is a cultural geographer at California State University, Northridge, USA. His research focuses on public space in North America and Japan.

He is also an author at The “Good Tourism” Blog.

In this “GT” Travel Experience I will recommend three such places:

Three places to go in Greater Tokyo

(And don’t miss my getting around tip at the end, which will save you a lot of hassle.)

1. Ministry of Defense compound, Ichigaya

After World War II, the United States ghost-wrote a new constitution for Japan that stripped the emperor of political and military authority, made the country a democracy, and, in its famous “peace clause”, forbade Japan from having a military.

Soon after the Constitution went into effect in 1947, however, fears of Communist armies invading east Asia prompted the US to rethink that commitment to peace. Exploiting a loophole, they allowed Japan to create a military clothed as the “National Police Reserve”.

The Reserve evolved into today’s “Self-Defense Forces” (SDF), a sophisticated military but one Constitutionally constrained to operate only within Japanese territory. (Their main enemy has been, in movies, Godzilla.)

Tourists can visit the SDF’s roughly 60-acre compound in Ichigaya, in central Tokyo, which features displays of military equipment, facilities, and historic buildings.

The most striking moment of the tour for me was entering the building that housed the former Ministry of War and, in 1946, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (i.e. the Tokyo War Crimes Trials).

Eerily, but fascinatingly for a fan of his novels, the tour also included the room upstairs where the writer-cum-reactionary-militant Yukio Mishima attempted a coup and then committed seppuku in 1970.

You might want to prepare for this part of the tour by reading some of the works that garnered Mishima five Nobel Prize nominations, or by watching the George Lucas/Francis Ford Coppola-produced movie Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters before you go.

Check the MOD website for details and to register for a tour in advance (if available).

2. Showa Kinen Koen (‘Showa Memorial Park’), Tachikawa

Americans may display a lingering anti-urban bias, romanticising rural life and opting for suburban homes, but the Japanese embrace urbanity. (They have little choice, with the population of 125 million squeezed into the mountainous country’s valleys and plains.)

Japan’s urbanism is urbanism squared, with the signature Tokyo intersections packed with pedestrians under frenetic neon skylines, trains whooshing past on trestles, alleyways thronging with shops and street vendors.

In that context, any park is notable simply for the solitude and greenery it offers. Tokyo has many famous parks and gardens, but a gem worth a bit of extra travelling to get to is Showa Kinen Koen, 35 kilometres west of downtown.

Built during the “golden era” of park creation of the 1970s-80s in Japan, when the country’s economic coffers were overflowing and the government invested heavily in parkland to serve dispersing metropolitan populations, Showa Kinen Koen is a lavish, 180-ha (445-acre) park meant to serve multiple metropolitan areas.

Designed to represent the “original” landscape of the Musashino plain, the park offers endlessly delightful exploration through a forest, “komorebi” (sun-dappled) hills, expansive flower beds, around a lake, and into a “village” of 1950s-era farm buildings around functioning rice paddies.

Most impressive to me is the award-winning “Children’s Forest”, which occupies a Lewis-Carroll-ish space of its own.

This area features a half-buried Mayan temple, mists that rise from hidden grates, dragons that swim out of the ground, and more that kids and adults alike will love. Fireworks light up the sky on summer evenings.

Interestingly, urban-explorer sleuths suggest that beneath Showa Kinen Koen is a vast, secret network of tunnels and spaces meant to house the government in case of a disaster. That possibility extends the park’s above-ground fantasy into subterranean “what-if” space.

The adjacent Tachikawa shopping district is crammed with restaurants and shops to explore as well.

3. ‘The Low City’, Kikuzaka

In his outstanding book, Tokyo: A Spatial Anthropology, urbanist Jinnai Hidenobu notes that Tokyo was never “Haussmannized”, or given a large-scale modernist makeover.

It was, instead, rebuilt more typically lot by lot.

Thus he writes of placing a historic map of Edo (Tokyo’s early-modern incarnation) atop one of modern Tokyo and finding that, beneath its skin of modern structures, many Tokyo neighbourhoods retain distinctive spatial patterns that were established centuries ago.

Jinnai tours the reader through several former high and low (elite and commoner) areas.

I followed Jinnai’s lead and visited the Kikuzaka neighbourhood in Hongo, formerly part of the low city. Here commoners lived in row houses separated by narrow alleyways, or kaisho, that formed micro-social worlds within what was by the 1700s perhaps already the world’s largest city.

Kikuzaka’s alleys are densely humanised with gardens, wells, and small shrines. Such were the public spaces of Edo; not a city of grand plazas, parks, and boulevards, but of small, hidden, social worlds.

Getting around

A tip: It’s a good idea to study Tokyo’s transportation network, and work out your routes, before you begin your trip. The system is a stringozzi-galaxy of multiple, separate bus and train networks that overlap into a truly colossal mega system.

The maps on the walls of Tokyo metro stations resemble Jackson Pollock-inspired murals, but you won’t want to indulge in art appreciation amidst the hectic crowds and busy timetables. You’ll want to have a solid plan of how to get from A to B.

Doing some homework beforehand, and buying a PASMO card that works across multiple systems, is a good idea.

Read more “GT” Travel Experiences in Asia

Featured pic (top of post)

Places to go in Greater Tokyo include Showa Kinen Koen. Pic by Norikio Yamamoto (CC0) via Unsplash.

Where is this?

The pin on the “GT” Travel map that represents this “GT” Travel Experence points to Showa Kinen Koen (“Showa Memorial Park”) in Tachikawa, western Tokyo.